KANSAS CITY, Mo. — Back in the mid-1800s, Kansas City was a sizable town. Irish immigrants who moved to the area sacrificed their time and strength to help develop the growing hub into a major city in the Midwest. They helped pave the streets, they cut into limestone, and they handled a terrain strikingly different from what we see today. A large portion of Irish immigrants moved to the United States during the Great Potato Famine in Ireland between 1845 and 1849. The majority of immigrants who traveled to Kansas by 1870 were from the British Isles, particularly from Ireland.

In 1871 an Irish priest in Leavenworth, Kansas wrote a pamphlet encouraging people to move from the European island to the Midwestern and landlocked state. The priest, Thomas Butler, wrote how Catholicism in Kansas changed throughout the 1800s. He wrote that with the advent of the large Irish immigration, the construction of Catholic churches in Kansas quickly increased. There were a total of three Catholic churches in Kansas in 1854 – by 1871 that number increased to 45.

From the late 1800s to the early 1900s, Kansas City housed one of the largest colonies of Irish immigrants in the nation. During the 19th century, the United States had a population of about four million Irish born residents.

Immigration, Famine, Poverty

In the 1830s and 1840s, German and Irish immigrants sought new lives and providence, but both groups were often too poor to buy land. The immigrants often settled in cities or urban sprawls to work as menial laborers. Immigrants during the 19th century arrived in large droves and would send money back to their families. This helped other family members emigrate from Ireland.

The main staple of the Irish diet was depleted during the Great Famine. More than one million people died in the country; however, the exact death toll is unknown and historians argue the data wasn’t well kept. Registration of births, marriages, and deaths hadn’t officially begun on the island. Records kept by the Roman Catholic Church were frequently incomplete. Several historians argue that most people during the famine died from diseases rather than starvation. The country did ship out residents to other places in hopes of saving people from starvation.

The Great Famine and the Napoleonic Wars are considered the two biggest factors for the loss of life in 19th-century Europe. The famine drastically changed the island’s demographic, political, and cultural landscape. Because of the famine the country produced some two million refugees – and had a century long population decline. The famine strained an already soured relationship between the Irish and the British Crown – this resulted in heightened ethnic tensions and Irish nationalism.

Could the famine have been avoided? According to British historian and biographer Cecil Blanche Woodham-Smith — it could have. She wrote four popular history books, each dealing with different aspects of the Victorian era. She calculated between 1801 and 1845 there had been some 114 commissions and another 61 special committees inquiring into the state of Ireland, and that “without exception their findings prophesied disaster; Ireland was on the verge of starvation, her population rapidly increasing, three-quarters of her labourers unemployed, housing conditions appalling and the standard of living unbelievably low.” In her book “The Great Hunger: Ireland 1845-1849” she was critical of Britain’s handling of the famine. She singled out Sir Charles Edward Trevelyan for neglecting the Irish people. She also noted the British government had assisted Ireland during the first phrase of the famine.

Ireland had a previous famine in 1782-83. During that time, the government shutdown the ports to keep Irish-grown food in Ireland to feed the people there. Local food prices quickly dropped, but Merchants were upset and lobbied against the export ban. The Parliament then exercised powers within the Constitution of 1782 to override the protests. Sadly, during the Great Potato Famine, there was no export ban. Some historians have argued because exports weren’t stopped, the famine was a consequence of the British government’s failure to retain necessary food in the country.

Irish residents during the Great Famine moved primarily to England, Scotland, South Wales, North America, and Australia. By 1851, a quarter of Liverpool’s population was Irish-born.

Younger members of families moved first. Immigration became almost a rite of passage. Irish women actually immigrated just as often as men did.

By 1850, the Irish made up a quarter of the population in Boston, New York City, Philadelphia, and Baltimore. The Irish also moved in large numbers to American mining towns and communities.

Irish Immigration and Kansas City History

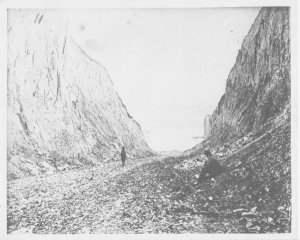

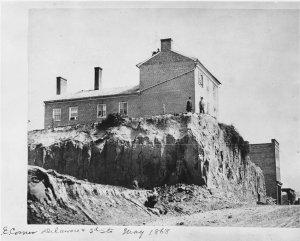

In 1854, the government opened up Kansas Territory to settlers. Several groups moved there with the hopes of developing unsettled land and to start a new life. Irish immigrants moved in large numbers to both Missouri and Kansas. As mentioned previously in the article, Irish men took on menial labor jobs. Developing the west required many strong workers who did arduous labor to craft cities. Kansas City was in large part built by the Irish immigrants. Some of the oldest archived photographs in the Missouri Valley Special Collections reveal a rough, dizzying landscape abundant with limestone. Westport and Independence thrived as primary departure points for travelers along the Santa Fe and Oregon Trails. These were also trading centers for fur trappers and Native Americans.

The invention of the steamboat helped with immigration efforts. It allowed for ease in transporting peoples as well as trading goods up the Missouri River. Before the steamboat, the only way people could reach the settlement was by slowly traveling overland against grueling wilderness. A natural stone wharf allowed steamers to unload near where the Kaw River connects into the Missouri River.

In 1857, Father Bernard Donnelly moved to Missouri to teach and spread Catholicism. He had a background in civil engineering. With his expertise in stone cutting and bringing groups together, he helped Kansas City become what it is today. He and several hard workers reshaped limestone and cut through stone bluffs to help pave the way for streets. They helped build and expand the growing hub based on the priest’s knowledge of quarrying and brick-making. The Father also used his theological training to attract the manpower necessary for cutting roads; he also advertised for laborers in newspapers and magazines read widely among Irish immigrants living along the East Coast.

In 1857, Edmond O’Flaherty was appointed as the City Engineer for Kansas City. The Irishman shares credit with Donnelly for leading the early grading and paving projects.

Irish workers hauled stones to build foundations, and they carried buckets of water to extinguish fires. The workers killed millions of cattle, they laid down miles of bricks and rails, and they also drove streetcars. The Irish kept and disturbed the peace, they organized the working poor, and they kicked down barriers at City Hall and the courthouse. They literally carved out the skyline for the city that we’ve built upon today. Donnelly and his team built canyon-esque streets. The upward expansion of homes and roads earned Kansas City the nickname Gully Town – a name that stuck for more than 30 years.

Irish and German immigrants moved to Kansas City to work in stockyards, manufacturing plants, warehouses, and meat packing plants. These jobs were rough and often came with low wages. A large portion of the community lived in shanty-towns across the bluffs – in one particular spot the living conditions were considered so horrible that people called it “Hell’s Half-Acre.” The impoverished site was a deluge of crime, prostitution, and dirty water. There was no sanitation in this shanty-town. The slums then were a dire, miserable place – often a reeking cesspool fueled by diseases. Many left for other parts of the metro or entirely different hubs as these dangerous conditions surfaced. There was a gross unhygienic fog that loomed over the low economic portions of most cities in the 1800s. Technological advances in both medicine and sanitation helped relieve some of these 19th century urban foils.

Father Donnelly saw to many of the housing needs, education, and spiritual concerns of the Irish who moved to Kansas City. He helped establish some of the earliest schools and orphanages. He advocated for temperance, a movement he had joined before traveling to the United States. He and his crew established Connaught-Town. The priest also helped develop the city’s original St. Patrick’s Day celebrations.

The Irish also moved west to help with the expansion of railroads, which was a booming industry at the time — even if it was back breaking. Many Irish immigrants followed the expansion of rails until eventually settling in hubs around the railroads.

In the 1870s, Ireland was hit with another economic depression. By this point, Kansas City was an attractive destination for Irish immigrants. By the 1880s, around 50,000 Ireland natives lived in Missouri. Kansas City was the only place in the state where Irish immigrants outnumbered German immigrants significantly.

Population Timeline of Kansas City

1846 – 700

1860 – 4,418

1870 – 32,260

Roughly 55,785 people lived in Kansas City in 1880. On the east side of the state, around 350,520 people lived in St. Louis. Around 2,168,380 people lived in the whole state of Missouri in 1880.

Prohibition and the Arrival of a Crime Boss

Kansas passed Prohibition laws in the late 1800s. Missouri was the second-to-last state to adopt these kinds of laws. Voter initiatives that supported Prohibition failed multiple times. Missourians voted for these initiatives to break away from political parties – which in Kansas City the parties were rife with corruption. Kansas City kept Prohibition laws at bay in part because of Tom Pendergast’s corrupt political machine. He scrupulously sought after immigrants and attracted them to the polls to vote for the Democrat candidate of his liking. When Prohibition hit Kansas City, it had little to no impact on the night scene. Pendergast kept a tight watch on a considerable amount of contacts, and he helped the speakeasies flourish.

During the 1890s, crime boss Pendergast moved to Kansas City to join his brother James. They were children of Irish immigrants. James lorded himself over the West Bottoms. Back then the area served as a major hub for the city’s warehouses, rail yards, and packinghouses. Several people scrambled for wages here – including African Americans, immigrants, and poor white workers. The West Bottoms struggled with poor infrastructure from crummy roads, lackluster sanitation standards, and overcrowded housing. Several Irish families controlled the politics of the time. The mafia had a strong base in Kansas City.

French immigrants originally settled in the West Bottoms. It used to be called the French Bottoms. The immigrants came to the area as fur trappers, and they connected with the Kansa tribe. With railways and an increase in warehouses and saloons – the French aspects of the district diminished.

Irish Heritage in the Present

Kelly’s Westport Inn and the adjoining Chouteau Store are considered the oldest buildings still standing in Kansas City. The popular Westport bar inspired Kansas City native Eddie Griffin to use it as the setting for his sitcom Malcolm & Eddie. It starred him and Malcolm-Jamal Warner. The bar was built around 1850. In 1959 it was designated as a national historic landmark. The grandson of Daniel Boone – Albert Gallatin Boone – opened up a grocery there at one point.

There are some rumors that the drinking establishment once had a tunnel running south connecting to a stable as part of the Underground Railroad.

Browne’s Irish Marketplace is the oldest Irish-owned business in the United States. It opened in Kansas City in 1887. Proprietors Ed and Mary Flavin emigrated from County Kerry, Ireland. They traded pennies for cured hams and embroidered pieces of lace. Flavin’s Market at 27th and Jefferson served as a hot spot for neighbors to meet. In 1901 the Flavins built a new store on the outskirts of town — the corner of 33rd and Pennsylvania.

The eatery today offers a number of Irish staples and delights from corned beef, Irish potato soup, and soda bread. The store offers apparel, jewelry, and home décor. You can find out more about Browne’s Irish Marketplace on its website, which includes its history.

Besides one of the largest St. Patrick’s Day parades in the United States, there is also the Kansas City Irish Fest. It is held over Labor Day weekend ever year in Crown Center and Washington Park.

This is only a brief overview of Irish immigrants influence on Kansas City and some of the struggles, achievements, and establishments from their journey here. You can find several books online that go into more detail about Kansas City’s history, Irish immigration, ancestry, and other related stories.

References:

Browne’s Irish Market, brownesirishmarket.com/deli/.

Church, Michael. Kansas Memory Blog, Laurel Fritzsch, Museum Curator, www.kansasmemory.org/blog/post/74315032.

KC HISTORY, Missouri Valley Special Collections at the Kansas City Public Library. How the Irish Laid the Groundwork for Downtown Kansas City, www.kchistory.org/blog/how-irish-laid-groundwork-downtown-kansas-city.

Scanlon, Heather. The Irish Way: Immigration And Innovation In Kansas City, www.squeezeboxcity.com/irishimmigration/.

Wikipedia: Great Famine, Cecil Woodham-Smith, Kelly’s Westport Inn