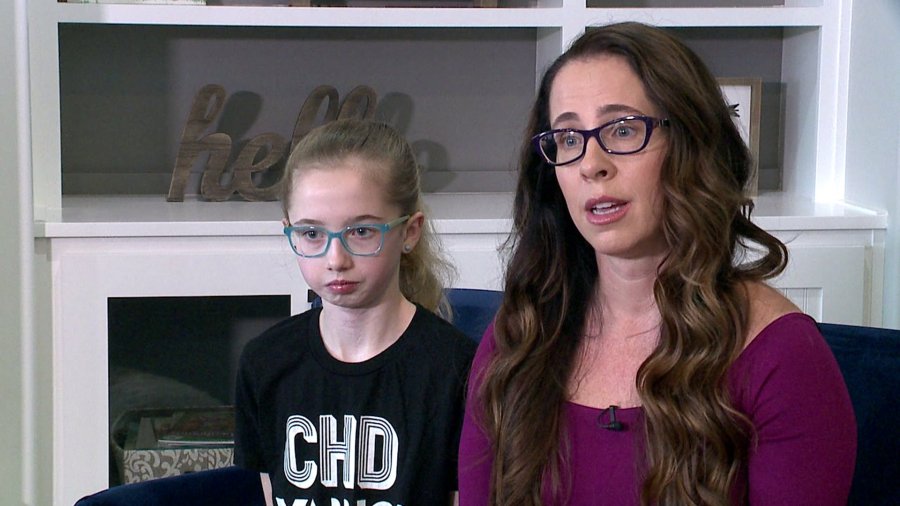

LEE’S SUMMIT, Mo. — Kelly Manz knows it sounds crazy when she describes what alerted her to her newborn’s problem. Little Chloe had already gotten a clean bill of health from a neonatologist, a pediatrician and every nurse that saw the infant.

“She looked fine. She didn’t have any signs or symptoms that anything was wrong,” Manz said. “But I had a horrible feeling.”

Chloe was just 9 hours old, about to spend the night with Manz in her hospital room. Manz called for a nurse. The nurse said Chloe looked fine. Fifteen minutes passed, and she called the nurse again.

“It was a voice in my head saying, ‘Something’s wrong. Something’s wrong with Chloe,'” Manz remembered. “And it just didn’t stop.”

Manz is thankful she didn’t give up. She insisted Chloe be taken to the nursery. Then Manz took a nap, woke up and called the nurse again.

“They said, ‘Well, actually, something is wrong with her. You’re right,'” Manz said.

In a matter of hours, Manz learned the baby that showed no problems in her womb would need open heart surgery just for a chance at life. Little Chloe had critical congenital heart defects. There wasn’t nearly enough oxygen in her blood.

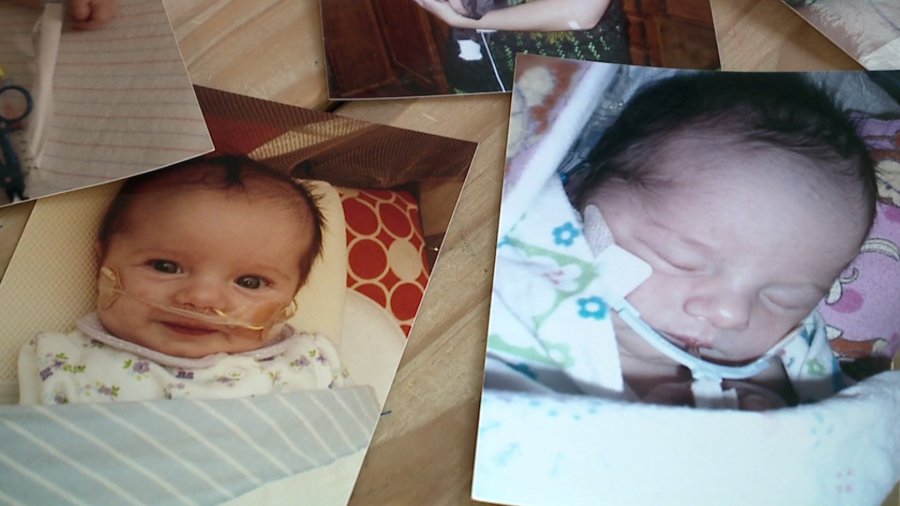

Chloe spent a month in the NICU. Once Manz brought Chloe home, she also brought oxygen tanks, feeding tubes and heart rate monitors.

Chloe needed to wait three more months before her first heart surgery. Then she had stomach surgery at seven months and neck surgery at 18 months.

The surgeries worked. Today, Chloe is a typical 11-year-old. She likes reading, gymnastics and playing outside.

“In the world of heart defects, we are extremely blessed,” Manz said.

Chloe’s positive outcome started with Manz’s intuition and insistence, but Manz didn’t want other parents to have to rely on instinct. She learned the hospital discovered Chloe’s congenital heart defect using a pulse oximeter: a common device that reads your blood oxygen level.

“They only used to put it on babies if the baby was in their care, in the nursery or the NICU,” Manz said. “Anyone else in the maternity ward or regular rooms– they wouldn’t get this screening.”

With the help of a pediatric cardiologist, Manz drafted Chloe’s Law. It requires every baby born in Missouri to get a pulse oximetry screening. Even if the baby is born at home, the person delivering the baby must get the test done within 48 hours.

“It saves lives. It absolutely saves lives,” Manz said.

While Manz was pushing to get Chloe’s Law passed, she was also sharing the bill’s language with families in other states living with congenital heart defects.

“I got on social media and just started reaching out to other heart parents, saying ‘You need to get this law passed,” Manz said. “Other families went and did the same thing so it spread.”

Between 2011 and 2019, 49 states and Washington, D.C. began requiring pulse oximetry screening for newborns. The only exception is California, where hospitals are still required to offer the screening.

After Missouri passed Chloe’s Law in 2014, Manz decided to raise money for other “heart families.” She started a 5K, Run for Little Hearts. It grew from 400 participants in 2014 to about 2,500 participants in 2019.

“We bond together over what we all have gone through,” Manz said. “A lot of the warriors– our little heart heroes– they say ‘This is my race! Its my day!'”

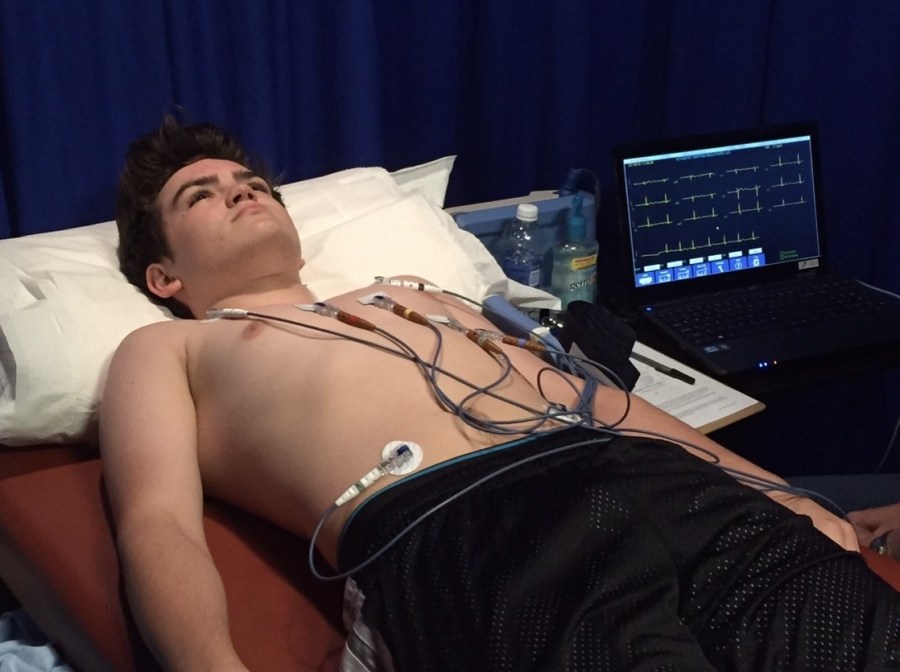

Besides Run for Little Hearts, Manz has organized free heart screenings in underprivileged parts of Kansas City. She also set up screenings for student athletes, where kids get an EKG and echocardiogram.

“I want to find these kids that have a hidden heart defect before it’s too late,” Manz said. “These kids don’t have any signs or symptoms, and they just collapse. It’s tragic, and it’s preventable.

As for Chloe, she will need another open-heart surgery sometime in the next year or two. But after seeing the photos of her first few months, she knows she’s in good hands.

“I’m not that worried about that,” Chloe said. “I know that my mom is going to help me through recovery since I’ve done it before.”