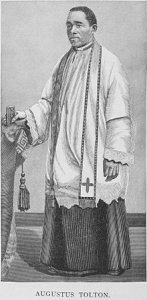

QUINCY, Ill. — The first black Roman Catholic priest in the United States could soon be canonized as a saint. Augustus Tolton had a short and challenging life. He was born April 1, 1854 in Brush Creek, Missouri into a slave family. Brush Creek is an unincorporated community in southern Laclede County in southwestern Missouri. The area is four miles southwest of Lebanon and about one mile north of Caffeyville. I-44 passes about one mile to the southeast.

The Vatican on June 12, 2019 said Fr. Tolton had taken a historic step toward becoming the first Catholic African-American saint. With the announcement, Tolton will be granted the title “Venerable.” The next steps to sainthood would be beatification, followed by canonization. Catholic Authorities in Rome will review a potential miracle attributed to the priest’s intercession. The Diocese of Springfield in Illinois said it has been working on the priest’s cause of canonization with the Archdiocese of Chicago since 2003.

“Father Tolton leaves us a shining example of what Christian action is all about, what patient suffering is all about in face of life’s incongruities,” said Bishop Joseph Perry, the Archdiocese of Chicago.

Pope Francis authorized the promulgation of a “Decree of Heroic Virtue.” This advances the cause of Augustine Tolton to sainthood. The title “Venerable” indicates Augustine lived the theological virtues of faith, hope, and charity and the cardinal virtues of prudence, justice, fortitude, and temperance at a high level.

Early Life and Early Inclinations toward Catholicism

Peter Paul Tolton and his wife Martha Jane Chisley raised their son Augustus just a handful of years before the Civil War started and during the conflict. The Tolton family lived as slaves on a property in Brush Creek. Martha named her son after an uncle. As a Catholic, she wanted to raise her children in the faith. Augustus was baptized under the name Augustine in St. Peter’s Catholic Church in Brush Creek.

It is not documented clearly how the Tolton family gained their freedom. Father Tolton told his friends and parishioners that his father was the first to escape, and his father joined the Union Army. Tolton’s mother later ran away with her children Samuel, Charley, Augustine, and Anne. Union soldiers and police helped the Toltons cross the Mississippi River and into the Free State of Illinois. Descendants of the Elliott family have reported that slave owner Stephen Elliot freed all his slaves at the outbreak of the Civil War, including the Tolton family.

Augustine’s father died of dysentery before the war ended. Dysentery was a disease of the time and often spread because of poor sanitation methods.

Life after Slavery and the Path to Priesthood

The Tolton family made their way to Quincy, Illinois. Some of the children, including Augustus, helped roll tobacco cigars for the Herris Tobacco Company. After his brother Charley died at a young age, Augustine met Fr. Peter McGirr, an Irish immigrant priest who took interest in youth education. The priest gave Augustine the opportunity to study at the St. Peter’s parochial school during the winter months when the tobacco company was closed. In a time rife with racial tensions, the priest’s decision was seen as controversial. The parish, like most in America, didn’t have a path for black boys and men to gain proper instruction for priesthood. Some abolitionists in Illinois objected to a black student at the school. Fr. McGirr didn’t fall prey to discriminatory claims, and he pushed harder to allow Augustine to study there.

Augustine proved to be a bright pupil. Several priests took him under their wing to grow his education. Unfortunately, every American seminary Augustine applied to rejected him. Fr. McGirr continued to believe in him and pushed for Augustine to continue his studies in Rome. Tolton graduated from St. Francis Solanus College and attended the Pontifical Urbaniana University, where he became fluent in Italian and learned Greek and Latin.

Augustine Tolton was ordained to the priesthood in Rome in 1886 at the age of 31. His first public Mass was in St. Peter’s Basilica on Easter Sunday in 1886. He intended to serve in Africa. He spent a large amount of time studying the continent’s regional cultures, languages, and main disparities. The Vatican had a different plan for him. The Church had Augustine return to the United States to help heal wounds and bring peace during a heightened time of racism and division. The Vatican wanted Fr. Tolton to serve the black community.

The newly ordained priest moved back to the Midwest. Augustine celebrated his first Mass in the United States at St. Boniface church in Quincy. Since it was previously his home and he was familiar with the area, he wanted to organize a parish there, but he was met with resistance from white Catholics and black Protestants. Though Fr. Tolton was respected by the black community, Protestants didn’t want Augustine attracting African Americans to another denomination. He later moved to Chicago and led a growing mission society, St. Augustine’s — it met in the basement of St. Mary’s Church. Augustine later developed the Negro “national parish” of St. Monica’s Catholic Church – the church eventually seated 850 parishioners. An impressive accomplishment even by today’s standards.

Fr. Tolton’s success at ministering to black Catholics earned him national recognition. Some parishioners referred to him as “Good Father Gus.” Several people in letters and other documents described his sermons as eloquent. Others praised his beautiful singing voice and talent for playing the accordion.

The priest unfortunately had several health struggles in his late 30s and into his 40s. He first became sick in 1893. He had to take a temporary leave of absence from his duties at St. Monica’s Parish in 1895. In 1897, at the age of 43, he collapsed from heatstroke and died. A powerful heat wave had taken over Chicago that day. One hundred priests attended a funeral for the late cleric. He was buried in the priests’ lot in St. Peter’s Cemetery in Quincy. He previously requested to be buried there as he still considered the city his home.

Examining Augustine Tolton’s Remains with Anthropologists

In February 2011, Tolton received the designation “Servant of God,” a title given to a candidate by the Vatican once a cause for sainthood has begun. The research phase of the cause concluded on September 29, 2014 with a special ceremony in St. James Chapel in Chicago. The ceremony included the signing, sealing, and binding of the dossier to be sent to Rome for further review and archiving.

The next phase of historical fact checking might seem grisly, but it ordered anthropologists to uncover and document the holy figure’s remains. The nihil obstat was granted to Bishop Thomas Paprocki of Springfield on June 21, 2016 to open the grave of Augustine Tolton. Beyond record keeping, this ensures canonical recognition of his remains. In the presence of Bishops Paprocki and Perry, Catholic Cemeteries for the Diocese of Springfield and the Archdiocese of Chicago exhumed his remains at St. Peter Cemetery in Quincy, Illinois. This took place on December 9 -10, 2016 with the assistance of a medical examiner, forensic and anthropologist specialists. Later in the same day, specialists re-wrapped the deceased priest with a new set of vestments and reinterred the remains.

“This goes back to a very ancient tradition in the church for a number of reasons. One was to document that the person really existed and wasn’t a figment of someone’s imagination or some group’s imagination. Finding their grave was the telltale sign that the person lived, breathed and walked this earth,” said Bishop Perry.

Before the excavation process, the team of grave diggers and diocesan officials gathered for an opening prayer service led by Springfield Bishop Thomas Paprocki. The Catholic Church has specific rules in regards to sainthood as well as uncovering remains. The rules could cover several volumes. The intent is to document and keep track of ongoing events as legitimately as possible.

“There is a canon law that they have to follow that lays out exactly what has to be done and how it’s done to the point that they called the workers together to swear an oath to diligence and professionalism,” said Roman Szabelski, executive director of Catholic Cemeteries of the Chicago archdiocese.

Using advanced technology, like sonar, they verified the grave’s location before digging up the cemetery. Crews dug 6 feet down into the soil to about 4 inches above the priest’s grave. Anthropologists removed dirt from a 6-foot-by-11-foot space.

Forensic specialists worked under a white tent to examine the skeletal parts. The designated space allowed crews to work and shield the delicate pieces from the elements, which could cause erosion or other problems.

The wooden coffin for Augustine had taken serious damage over the years. Natural movements from the earth had crushed the coffin. The casket clearly used to have a glass top because workers found broken glass mixed with the remains. Funeral coordinators in the past often selected glass-topped coffins for people of position or for well known figures.

In addition to the corpse, the team found metal knobs and wood from the coffin, parts of a crucifix and rosary, and a portion of Fr. Tolton’s Roman collar.

“The intent of all of this is preserving the remains we have of a possible saint. We want to make sure that anything that we find is preserved, so it will go into a sealed casket and from the sealed casket into a sealed vault,” said Szabelski told the Catholic New World, Chicago’s archdiocesan newspaper.

Anthropologists intentionally slowed down the digging process to preserve the corpse. Crews used special trowels and soft brushes to carefully unearth the remains.

A forensic pathologist pieced the bones together anatomically while crews uncovered more pieces. In addition to the skull, diggers found Tolton’s femurs, rib bones, vertebrae, collarbones, pelvis, parts of the arm bones and other smaller bones.

The forensic pathologist used the skull to verify the remains were a black person’s. He also determined by the shape and thickness of bones in the pelvic area that the remains belonged to a male in his early 40s.

After the team uncovered all the artifacts and documented the conditions of the parts, they immediately began the process to reinter Fr. Tolton. Priests vested the remains with a white Roman chasuble and maniple, amice, and cincture. They placed the items in a new casket bearing a plate that identified him as “Servant of God Augustus Tolton,” along with his dates of birth, ordination, and death. A document left in the coffin details the work anthropologists and clergy did that day.

At this time, so far two miracles are possible and have been sent to Rome for further scrutiny.

On the Pathway to Sainthood

Before reaching sainthood, historical consultants completed an approval of the Positio of Tolton’s life. The Positio, an official position paper, summarizes the examination of a candidate’s life, ascertains the person as historical and not fictional, and evaluates the person for heroic virtue or martyrdom. Historians assembled the Positio on Tolton through a compilation of documents, records, publications, letters, newspaper clippings, and historical facts of the era in which he lived, and through the testimony of clergy, religious and laity who could vouch for his reputation in the Catholic community as a holy figure. Six historical Vatican consultants ruled unanimously on March 8, 2018 in favor of the Tolton Positio, which was based on more than 100 pages of research completed in Chicago.

Theological consultants of the Congregation of the Causes of Saints unanimously voted on February 5, 2019 for the beatification and canonization of The Servant of God Reverend Augustine Tolton. According to the consultants, once a miracle has been confirmed through the intercession of Tolton, he will be declared “Blessed.” For canonization, a second miracle will likely be required.

One of the people pushing for Augustine Tolton’s sainthood is Most Reverend Joseph N. Perry, the auxiliary bishop of Chicago and diocesan postulator for the Tolton cause. Perry said Tolton’s story needs to be remembered because it is still applicable to current struggles in society.

“Lessons from his early life as a slave and the prejudice he endured in becoming a priest still apply today with our current problems of racial and social injustices and inequities that divide neighborhoods, churches, and communities by race, class, and ethnicity. His work isn’t done. We will continue to honor his life and legacy of goodness, inclusivity, empathy, and resolve in how we treat one another” said Bishop Perry.