CHERRYVALE, Kan. — Kansas, in its earliest history, was a haven for violence and bloodshed. Intense rivalry between abolitionist and pro-slavery forces earned the then territory the nickname “Bleeding Kansas.”

Years after slavery ended, southeast Kansas still maintained a reputation as a violent and distressing place to live. One early case of deception has remained unsolved.

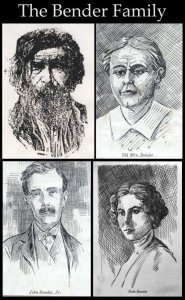

The murdering “Bender Family of Cherryvale” consisted of a mother, a father, a son and a daughter who settled into the infinitesimal prairie community back in 1870. They’re considered America’s first family of serial killers.

They also are infamous for disappearing into thin air.

In the isolated and vigilant old west

Cherryvale is in southeastern Kansas about 20 miles north of the border with Oklahoma. In the present, the town is allocated to Montgomery County. It’s home to a slew of museums.

The last real footnote from the city’s website is in 1987. That’s when the National Register of Historic Places included in its listings the town’s brick factory buildings, its Carthage cut stone pillars, a concrete foundation, some oak floors, and some beamed ceilings.

Cherryvale boasts a population of some 2,360 people. It’s about 150 miles southeast of Kansas City. The town is kind of in the middle of nowhere — the closest larger hub to it is Joplin about 75 miles east.

The Bender family left an ominous stain on Cherryvale and the surrounding area. The Bloody Benders included: John, Sr., his wife Elvira, their son John, Jr., and their lovely daughter Kate. There are no documents available that confirm where the family emigrated from, but it is widely speculated they came from Germany.

Some have questioned whether John and Kate were actually siblings but were instead husband and wife. There’s also rumors that Elvira got into the murder business before she married John Bender — and that she killed her previous husbands.

Homestead as a grifting and murder trap

In October 1870, five families of spiritualists settled in and around the township of Osage in northwestern Labette County, which is about seven miles northeast of where Cherryvale would be established seven months later.

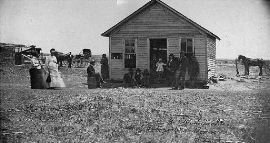

The Benders built a small inn for travelers crossing the Osage Trail — it was the only route at the time for traveling further west. They offered shelter and food for guests and their horses. The Bender men registered some 160 acres of land. The family also setup a general store where they sold dry goods.

Inn keeping was a lucrative business in the late 1800s, but it wasn’t enough for the Benders. They supplemented their income by taking advantage of their guests.

Historians argue that when travelers entered their home, the Benders would position themselves at a dinner table with their backs to a canvas curtain. They had a special chair where the traveler, the guest of honor, would sit.

The guests often got caught up in conversation with the young and attractive Kate. The parents spoke little English, but the second generation, who was approximately in their 20s, could speak it proficiently. The son had a slight German accent, and people often underestimated his intelligence for the way he sounded.

During the conversations with Kate, the unsuspecting traveler would be taken over by one of the two Bender men. A hammer brutally came down multiple times on the skull of the guest until the person died. The women then slit the victim’s throat.

After the attack, the four Benders would loot the body for money and other possessions. They would mutilate the body and dump the remains through a trap door into a cellar beneath their house. During the night, the family would move the body and bury it in a nearby apple orchard.

Cravings for more money and bloodshed

The elder Benders mostly kept to themselves, but the adult children regularly attended Sunday school in nearby Harmony Grove — they likely wanted to learn more about their neighbors and to scope out new victims.

By 1873, reports of missing people became so common that travelers avoided the trail through the Osage township. The area was known for horse thievery and violent crimes. Law and order was thin — vigilance committees took matters into their own hands dolling out justice willy-nilly.

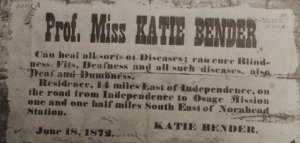

The Benders craved more victims and eventually targeted Cherryvale’s locals and not just the travelers. Kate hung up posters in town claiming she had supernatural powers that could heal blindness, deafness, and other ailments. She also claimed to be a psychic who could communicate with the dead. She called herself “Prof. Miss Katie Bender.” She gained notoriety for conducting séances and for advocating free love. People heard rumors about the attractive woman and this put the bed and breakfast into the limelight.

Those who fell for the poster bait became victims of the Bender family. They murdered at least 11 people. It’s probable they killed more than 20 altogether.

It’s important to keep in mind that the widespread national attention on the Bender family in the late 19th century makes it difficult to separate fact from fiction. Today we’re left with a handful of documents and artifacts to piece together. This makes the story elusive — but the Bender family when they were living was difficult to peg down.

The Kansas City Times described the discovery of one of the victim’s bodies as grisly:

“The little girl was probably eight years of age, and had long, sunny hair, and some traces of beauty on a countenance that was not yet entirely disfigured by decay. One arm was broken. The breastbone had been driven in. The right knee had been wrenched from its socket, the leg doubled up under the body. Nothing like this sickening series of crimes had ever been recorded in the whole history of the country.”

A couple of men narrowly saved themselves from death. William Pickering refused to sit with his back to the curtain canvas because it had stains all over it — and at the height of a seated man’s head. Kate Bender became angry when he didn’t follow directions — she threatened to kill him with a knife. He somehow escaped and lived to tell his tale.

A Catholic priest stopped by the inn to tend to his horse. He saw one of the Bender men hiding a large hammer in a room, so he left quickly.

A well-known doctor disappears

After a prominent local doctor disappeared in 1873, residents started to suspect something questionable was happening at the Bender property.

Dr. William Henry York had gone to question homesteaders along the trail after his neighbors George Newton Longcor and his infant daughter disappeared. They had lived in Independence, Kansas about 11 miles southwest of Cherryvale. Dr. York reached Fort Scott, and on March 9 he went on a journey back to Independence, but he never made it home.

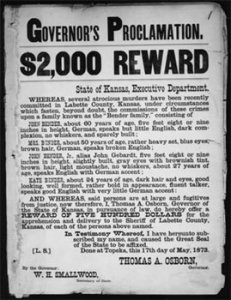

The doctor’s brothers were powerful people — Colonel Ed York living in Fort Scott and Alexander M. York, a member of the Kansas State Senate. Both knew about the doctor’s travel plans, and when he failed to return home, they had an all-out search for him. Colonel York led a company of some fifty men. Together they questioned every traveler along the trail and visited the homesteads along the route.

On March 28, 1873, Colonel York arrived at the Benders’ bed and breakfast inn. The Benders told the colonel the doctor had stayed with them; they suggested he may have run into trouble with indigenous tribes. The colonel didn’t investigate further that day.

On April 3, the colonel returned to the inn with a small army after hearing about a woman who escaped from the inn after Elvira threatened her with knives. Elvira acted like she couldn’t understand the accusation made against her because of her limited English, but the younger Benders denied the claim.

When the colonel repeated the story about the knives, Elvira allegedly became aggressive. She accused the female guest of witchery claiming she had cursed her coffee. Elvira ordered the men to leave the property — this was the first time they got the sense her English was better than she portrayed.

The Weekly Kansas Chief posted the following in an article on May 22, 1873. The article is kept in the Library of Congress.

“While going and coming from the creek, John told Col. York that his sister Kate could do anything, that she could control the devil, and that the devil did her bidding. When they returned to the home, Col. York tried to induce this wonderful mistress of the devil to reveal where the body of his brother was. She positively refused her satanic aid at this time, giving at her reason therefore that she could not do so in the day time, and while there were so many men and so much noise about.”

The article continued that before Colonel York left, Kate persuaded him to return Friday night; she suggested she could use her clairvoyant abilities to find his brother. He denied this request. The colonel and the small army were under the impression that the Benders and a neighboring family, the Roaches, were guilty in the string of disappearances. They wanted to hang the whole lot of them, but the colonel insisted they find evidence first.

Around that time, neighboring communities became increasingly concerned with the evolving number of malevolent accusations in the area, particularly around disappearances. The Osage township scheduled a meeting in the Harmony Grove schoolhouse. At least 75 people attended the emergency meeting, including Colonel York and both John Bender, Sr. and John Bender, Jr.

The community agreed that a search warrant would be obtained to search every homestead between Big Hill Creek and Drum Creek. They hoped a full examination of the area would solve the crisis.

The Bender family got word that people suspected them of nefarious play; they up and left days before anyone noticed their absence. Rancher Billy Tole noticed something was wrong when he was driving cattle past the property: the Benders’ animals appeared sickly and unfed. He alerted others.

Secrets left at the abandoned property

Several days lapsed before investigators combed through the Bender property — in part because of bad weather. The search party included Colonel York. The group found the Bender property empty of food, clothing, and personal possessions. A bad odor lingered from the trap door underneath a bed; it was nailed shut. After opening the trap, the team found a blood splattered room — the floors in particular needed serious cleaning. The team broke up the flooring — they didn’t discover any bodies or remains there.

The Kansas City Times wrote an article that described the initial investigation. The article detailed the trap door and pit beneath the Benders’ home:

“[The men] groped about over these splotches and held up a handful to the light. The ooze smeared itself over their palms and dribbled through their fingers. It was blood–thick, fetid, clammy, sticking blood–that they had found groping there in the void. Blood perhaps, of some poor, belated traveler who had laid himself down to dream of home and kindred, and who had died while dreaming of his loved ones.”

Detectives discovered more than a dozen bullet holes in the roof and on the sides of the cabin — many have speculated that some of the victims tried to fight the Benders back.

Authorities found eleven shallow graves in the apple orchard. The nature of the murders became clear as the search party excavated the graves. The crew first found Dr. York’s body — his feet barely underground. They also found George Longcur and his infant child.

Almost all the bodies had similar injuries: heads bashed in with a hammer and their throats cut. A young girl’s body had no injuries severe enough to cause death — investigators speculated one of the Benders strangled her or buried her alive. Some historians theorize the Bender family killed people not just for money but for sport.

Word of the murders spread through newspapers. Reporters from as far away as New York City and Chicago visited the property, but it’s unknown what exactly happened to the Bender family from there.

A Weekly Kansas Chief article described the garish setting in pristine detail:

“On last Sunday, there were about one thousand men, women, and children at the Bender grounds, gazing with mingled emotions of horror and curiosity. The graves even yet sent forth a sickening stench, and women held their noses as they peered down into the narrow tenantless holes.

Two special trains were run, one from Independence and one from Coffeyville, to a point on a railway line about two miles from the house, and teams were busy running to and from the house, and teams were busy running to and from the cars to the grounds, while the greater portion of the crowd was compelled to walk: these trains brought about 600 persons. There were about six or seven hundred persons from all parts of the surrounding country, in wagons, carriages, buggies, and on horseback.

The curiosity of many seemed to master their repulsion, and hundreds brought away some memento of the dreadful place. The blood-stained bedstead was smashed to pieces and divided in the crowd, all the shrubbery and young trees were broken or torn up and carried away, and pieces of the house torn off by the curious. Such another raid would not leave much of the shanty.”

Never finding the Benders

Detectives worked for years to try to find the Benders. Early in the investigation they discovered the Benders’ wagon. It was abandoned with a starving team of horses on the verge of collapsing outside the city limits of Thayer — a town about 12 miles north of the bed and breakfast.

Records indicate the family bought train tickets in Thayer for the Leavenworth, Lawrence & Galveston Raildroad for Humboldt. At Chanute, about 15 miles north of Thayer, the siblings left the train and caught the MK&T train south to Red River County, near Denison, Texas. The siblings traveled to an outlaw colony somewhere between Texas and New Mexico. Authorities didn’t pursue the pair — officers who followed outlaws into this region were often killed or never returned home.

A detective claimed he traced the pair to the border where he found John Jr. died of apoplexy — a sudden death often resulting from a cerebral hemorrhage or stroke.

The elder Benders did not leave the train at Humboldt. Records indicate they continued north to Kansas City; they likely bought tickets there and headed to St. Louis.

Police arrested several people over the years matching descriptions of the Bender family. In 1884, police arrested an elderly man in Montana. They accused him of murdering someone by using a hammer on the person’s head in Salmon, Idaho. The man matched a description similar to John Sr., Bender. It was never confirmed if he was that man — a deputy from Cherryvale went to look at the detainee, but the suspect had severed off his foot to escape irons. He bled to death. By the time the deputy arrived, decomposition had already made it too difficult to identify the person.

A Salmon saloon displayed his skull with the caption “Pa Bender” — that was until prohibition forced the pub’s closure in 1920. The skull was lost to time.

In the early 1880s, authorities took two women into custody. Officers brought the ladies to Kansas from Illinois, but police released them shortly. They found it was impossible to prove whether they were in fact part of the murderous family.

Remaining artifacts from the “devil’s kitchen”

Today little remains of the original site. Authorities destroyed the inn shortly after the discovery of the bodies. Souvenir hunters combed through and dismantled the building. A marker does stand on U.S. 169, near the former site. The sign describes the fate of the Benders as “one of the great unsolved mysteries of the Old West.”

A search of the Bender property turned up three hammers: a shoe hammer, a claw hammer, and a sledgehammer. The items matched indentations in some of the victims’ skulls. The son of LeRoy Dick, the Osage Township trustee who headed the search of the Bender property, donated the hammers to the Bender Museum in 1967. The Cherryvale Historical Museum now has those artifacts in a wall-mounted display case.

Colonel York reportedly found a knife with a four-inch tapered blade inside a mantel clock in the Bender House. In 1923, his wife donated the knife to the Kansas Museum of History in Topeka. The knife has reddish-brown stains on the blade. Upon request, visitors may see the weapon. The Kansas Historical Society has a podcast up on their website about the knife.